MT. KYOGAKURA

This tiny Shugendo peak and how the Japanese language got three alphabets

Jump to: My Kyogakura-san Hiking Guide

Although you cannot really blame me, to be honest, I’m a little bit disappointed in taking so long to discover Kyogakura-san. I mean, I’ve been to Juninotaki Falls at least a dozen times, it’s just that no one ever told me that in the hills directly behind one of Yamagata Prefecture’s most famous waterfalls lay such an intriguing mountain with a vastly rich Shugendo past

If I hadn’t started my 100 Famous Mountains of Yamagata project, I wouldn’t have known that such a dynamic little mountain existed only a short 20 minute drive from my doorstep. In this way, Kyogakura-san is a symbol of exactly why this project was instigated in the first place; to find little-known gems in my own backyard, and share them with the world.

And what a gem Kyogakura-san is!

From the Monkey Crossing to the Womb Pass, Zazen Rock on which countless Shugenja have meditated, and of course the peak’s namesake, the Kyozuka mound of sutras, Kyogakura-san is simply bursting with scintillating places to explore.

Why is Kyogakura-san the mountain of sutras?

So, what’s the connection between Kyogakura-san and sutras? It so happens that way back before the end of the Heian period (794 – 1185), a pile of Buddhist sutras was discovered in a mound near the summit. There a giant boulder lies with a gap barely big enough for a person to squeeze through. Sometime before Kyogakura-san was Kyogakura-san, someone placed Buddhist sutras praying for peace and tranquility and a bumper crop in a Sueki earthenware pot, and put it inside this gap.

I hope this person got their peace and tranquillity and a bumper crop in the end. Either way, their actions did lead to the naming of the mountain; Kyogakura translates to ‘a storehouse for sutra’, referring to this exact mound.

Buddhist Sutras and the connection with Japanese alphabets

Often found in written form, sutras are essentially truths or principles found in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. In fact, Buddhist sutras are at least partially why the Japanese language has three alphabets. Sutras originally written in Sanskrit were translated into Chinese, and then came to Japan when Buddhism was brought here starting around the middle of the 6th century.

Then, Japanese sounds were appropriated to the Chinese characters along with the native Japanese words, forming what we now know as Kanji (which literally means Han Chinese characters). That is why Kanji characters in Japanese have two types of readings; the original Chinese reading, known as on-yomi, and the original Japanese reading, known as kun-yomi. This also explains why the numbers 4 and 7 both have two readings in Japanese, yon and shi, and shichi and nana, respectively.

Interestingly, finding the on-yomi and kun-yomi is one way you can find out whether words are Japanese or Chinese in origin. One example my Yamabushi Master, Master Hoshino, gave me was the word for death, Shi (死). This word only has an on-yomi, which shows that death as a concept didn’t exist in ancient Japan. As far as we’re aware, it was believed that the dead still lived alongside us in a different part of this world, most often said to be the mountains, a common belief here in the Shonai region of Yamagata.

How did Hiragana and Katakana develop?

Unlike Chinese, Japanese is a polysyllabic language. To more easily be able to write the Japanese syllabary, a system called Man’yogana developed whereby traditional Chinese characters were used exclusively for their sounds, essentially forgoing meaning completely. For example, the Chinese characters 安 and 阿 were used to represent the sound ‘a’ (あ) in Japanese.

However, multiple Kanji were used to represent the same sounds, and Buddhist monks had to painstakingly write out whole Kanji characters to transcribe oral teachings. Before long, cursive forms of these characters were standardised and used instead, and the Hiragana alphabet was born. The Buddhist monks then used parts of Chinese characters to form the Katakana alphabet. Over the years the characters went through quite a few changes, but this is how written Japanese as we know it today was born.

Why copy Buddhist sutras?

Memorising, reciting, and copying Buddhist sutras is seen as a meritorious activity. Not only do sutras go some way in spreading the beliefs of Buddhism, copying them is also seen as a way of embodying the lessons of Buddha. Shakyo, as copying sutras is known, is still a very common practice in Buddhist temples around the world. Some also opt for Shabutsu, copying pictures of Buddha such as Kan’on Bosatsu (Avalokiteśvara) for the same effect.

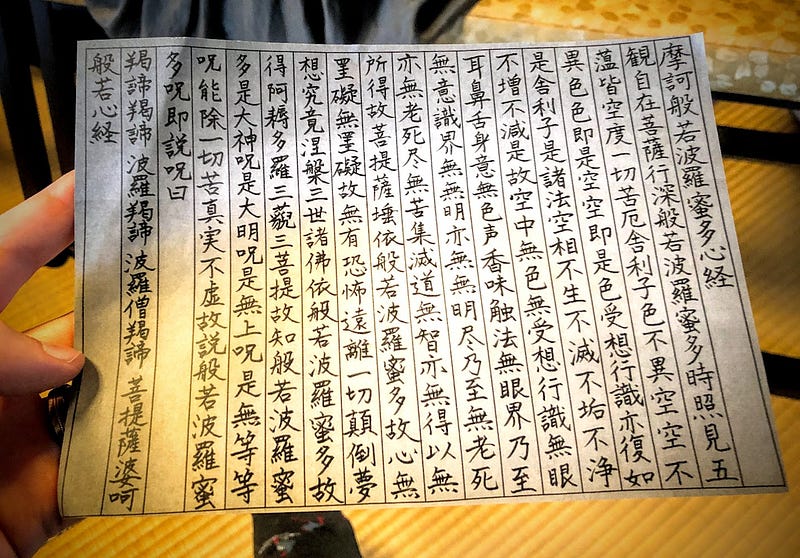

While the Lotus Sutra is quite popular, I believe the most common sutra, and therefore the most common sutra to copy, is The Heart Sutra (般若心経 Hanya Shingyo in Japanese). The Heart Sutra is the realisations Buddha had when he reached enlightenment. For those who are curious, the main teaching is that form is nothingness, and nothingness is form.

The realisations were so many that it takes at least 60 10-cm thick tomes just to contain The Heart Sutra in full. This would literally take an age to read, but thankfully there is an abridged version that takes about 2 to 3 minutes to get through. Naturally, this abridged version is what people prefer to copy.

One Fun Way Zen Monks Absorb the Lessons of Buddha

The monks of Zenpoji Temple, a Soto Zen sect monastery in Tsuruoka City, are famous for completing a ritual whereby they ‘read’ the full version of The Heart Sutra multiple times each day. By ‘read’ I mean in a group they hold up each of the 60 10-inch thick tomes one by one, and let the pages fan down in a way that generates wind. From this wind, the monks are able to ‘absorb’ the lessons from Buddha himself.

This ritual alone is worthy of a visit to Zenpoji Temple, although there is certainly much more to explore there. Ask to try meditation in their meditation hall, or try your hand at calligraphy for starters.

The Heart Sutra in Yamabushi Trainings

Incidentally, the Heart Sutra is also a huge part of our yamabushi trainings with Master Hoshino. Master Hoshino’s training might just be the only one left on the Dewa Sanzan to combine Shugendo chants with both Shinto and Buddhist chants, the original way it was done before the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In addition, The Heart Sutra is often what we chant while doing waterfall meditation, which gives you an indication of how long we stay under.

Moreover, once each year, people with an affinity to Daishobo pilgrim lodge, the pilgrim lodge run by Master Hoshino, spend hours on end reciting The Heart Sutra at Prince Hachiko Shrine at the summit of Haguro-san. Over the course of about three days in May (the earliest time it could be started), we all take turns to recite the Heart Sutra for hours on end as a way to pray in memory of those who lost their lives during the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011.

Memorising the Heart Sutra

In all, it took me over a year to memorise the Heart Sutra, as that’s how long it took me to take memorising it seriously. I thought I would be able to remember it during Yamabushi training alone, but that wasn’t the case and I ended up using my time in the bathtub over a whole winter to really nail it down.

Personally, I am really glad that I have memorised the Heart Sutra, not only because it is extremely useful during Yamabushi trainings and temple visits in Japan, but because it is something to fall back on when you want to try and relax or concentrate deeply, or just zone out.

For example, sometimes if I am trying to meditate but I’m just not feeling it, I recite the Heart Sutra. When I am trying to take a cold shower or some other challenge, I often recite the Heart Sutra to help me get through. In other words, it is definitely worth making the effort to memorize.

My Favourite Versions of the Heart Sutra

You can hear copies of us reciting The Heart Sutra recorded professionally by Matt Eric Hart of the British Library on this page (search for Yamabushi). There is also a recording of the Dalai Lama reciting the Heart Sutra in the original Sanskrit that I really enjoy, and this version of the Heart Sutra with monk DJ music is also quite inspirational.

Hiking Kyogakura-san

Now back to Kyogakura-san. My 100 Famous Mountains of Yamagata project is as much about discovering new places as it is me being a guinea pig for others. The majority of the mountains I’m visiting, I’m visiting for the first time, and besides the major mountains of Yamagata, basically none of them have any information in English, so I see it as my job to remedy that.

Which is exactly why I should have done more research on Kyogakura-san the first time I climbed it. That’s right. To bring this article to you, I ended up climbing Kyogakura-san twice. Thank Kami Kyogakura-san is the closest mountain on the list to my house. Either way, I’m pretty sure this means I am able to give a fair account of both trails.

Kyogakura-san and Haguro-san

I can’t help but compare Kyogakura-san to the Dewa Sanzan’s Haguro-san. Although the two mountains have a totally different atmosphere, with Haguro-san’s stone stairway amongst the cedar forest, and who could forget the Five Story Pagoda, the two mountains share a similar height and climb time, a famous waterfall at the base, a whole lot of stairs, and more importantly an extensive history as a mountain for Shugenja, these days known as Yamabushi.

In addition, much like the two trails up Haguro-san, i.e. the stone stairway and the ancient path of Haguro called the Haguro Kodo, Kyogakura-san has two main trails; The southern Ennoji Trail, and the northern Juninotaki Falls Trail. Both trails start on either side of a hill and meet at the summit of Kyogakura-san in an inverted ‘V’ shape. Depending on how you want to climb, it’s possible to do both sides with or without a car to help you.

Getting to Kyogakura-san

Kyogakura-san is located to the south-east of central Sakata, and the only realistic way to get there is by car. There are busses that go out that way, but they are few and far between. In saying that, it would also be possible to bike out this way. In fact, Juninotaki Falls is a very popular destination for cyclists in the Shonai region. I’m just not sure they also hike Kyogakura-san, but that would be a good challenge indeed.

The Recommended Way to Hike Kyogakura-san

I found this out after returning home the first time, but there is a recommended way to hike Kyogakura-san. It turns out that the best way is to take two cars, drop one car off at the Juninotaki trailhead, then drive to the Ennoji Trailhead and hike to the summit. Come down the Juninotaki trail, then use the car dropped off at the Juninotaki trailhead to pick up the other car. Alternatively, there is a bus that you can use to get between the trailheads.

If you have no friends or lack the ability to drive two cars at once, the only way you’d be able to do that is by timing the busses, and for such a rural location, I doubt the busses are frequent enough. Best to trick or bribe someone to be your friend, maybe promise them enlightenment or something.

My personal recommendation for solo hikers up Kyogakura-san

My recommendation for solo hikers or people with only one car would be to first hike to the summit of Kyogakura-san from the Ennoji side stopping at the sights along the way. Then, go down the trail to about the eighth station on the Juninotaki side where the Shumidan Rock is. Take in the view of Chokai-zan, then return to your car using the Ennoji Trail again. Once back, it is worth driving to Juninotaki Falls and checking it out on its lonesome. The waterfall is not very far at all from the car park, and is always an impressive spot to check out.

The Ennoji Trailhead up Kyogakura-san

Ennoji is a tiny hamlet on the edge of a valley of rice fields located in eastern Sakata City. If you make your way to the location on the map, there is a small road that leads into the mountains, and enough space for five or so cars to park. Keep following this road up and you will see the trailhead leading off into the mountain with the 一合目 ‘Ichigome’ sign for the first station. Here there is a little brown box with a counter inside to collect the number of climbers up the mountain. I was number 14, which I can only assume means for the month (I climbed on September 7).

Mountains in Japan often have stations such as these. Generally speaking, there are ten evenly-dispersed stations, with the tenth being at the summit. Gassan is an exception as the stations are not evenly distributed, but Kyogakura-san follows this rule.

From the first station it’s basically an ascent up a whole load of stairs that leads right up to the summit, with a few rest spots of course. Thankfully the whole path is inside a really awesome forest, so you have plenty of opportunity for Shinrinyoku forest bathing, and it helps to keep you cool the whole way. From the second station (二合目)there is a view to a nearby mountain, which I believe is the Juninotaki Trail. The next two stations are largely uneventful, but the fifth station was quite interesting indeed.

The Monkey Crossing

The fifth station is at a location called Saru Watari, which means ‘Monkey Crossing’. Here there is a giant rock wall that apparently even wild monkeys struggle to climb, AKA the perfect location for some Shugendo training. Not feeling brave? Well, just take the stairs on the normal path like I did (I do not recommend attempting to climb up this wall. If you fall down, you will fall quite far and may well do some damage to not only yourself, but the vegetation as well).

The Womb Pass: Why is there a ‘Womb Pass’ in the middle of Yamagata?

A little further up the path near the 6th station is the Tainai Kuguri ‘Womb Pass’. Unfortunately this path was blocked off so I couldn’t check it out, but at a guess it would probably be a huge set of rocks that you pass through, which symbolises, well, being born.

You may be wondering why there would be a place with such a name in the middle of the mountains of Yamagata. Well, in Shugendo there is a belief that the mountains are the world from before we were born, where all of life’s secrets are held.

Yamabushi train in the mountains to learn these secrets from nature. This is the main reason why we can’t discuss what goes on during yamabushi training, we simply are not supposed to have a memory of it. During yamabushi training, we enter the mountains and undertake a number of rituals designed to master nature and strengthen our souls. For the Yamabushi of the Dewa Sanzan, these rituals are based on The Ten Realms of Buddhism. Then, when we emerge from the mountains, the feeling is so euphoric it is akin to being reborn.

Meet the Mother of the Mountain

Naturally, this means that the mountains are the mother, and there are many references to childbirth and being reborn in locations with an affinity to Shugendo, such as the Dewa Sanzan and Kyogakura-san.

Incidentally, in Japanese the word for ‘the main path to the shrine or temple’ is Sando (参道, think Omotesando in Tokyo), which is a homonym for birth canal (産道). Usually, it works out that the Sando marks the final part of our yamabushi training, the point before we officially emerge reborn. I don’t believe this is a coincidence.

Zazen Rock (The Nozoki Rock)

After the eighth station, the path veers off and there is an opening that you do not want to miss. Known as the Zazen rock, here lies a huge boulder that offers expansive views over the surrounding mountains. In the past, this rock was such a popular location for monks to sit and meditate, it was named the Zazen (seated meditation) rock.

Another name for this rock is the Nozoki (peeking) Rock. I have nothing to back this up, but this may be from the Nozoki ritual in Shugendo. Nozoki is a common ritual in other Shugendo areas such as Omine and Kumano whereby yamabushi have rope wrapped around their torso and are suspended over a cliff face. The Nozoki ritual symbolises the Buddhist Hell Realm, one of the Ten Realms of Buddhism from earlier. On the Dewa Sanzan we have an entirely different ritual for the same purpose, but unfortunately I cannot share the details, you’re just going to have to join me on Yamabushi training!

Kyozuka: The Mound of Sutras

Keep following the path up from the Zazen rock and eventually there will be a giant rock face with a really cute Jizo statue tucked neatly inside. Just past this lies the mountain’s namesake, the Kyozuka mound of sutras.

The Kyozuka is a giant rock with a huge gap in the middle. While there are bars over the gap now to stop people climbing inside, it’s obvious that this is a sacred location, with a small shrine-like round earthenware pot in the centre. Inside this pot was where more than 800 years ago sutras praying for peace and tranquility and an abundant harvest were discovered. It really makes you wonder what life would have been like all those centuries ago.

The Summit of Kyogakura-san

Once you pass the Kyozuka, the summit is only a few minutes’ hike. The summit has a lookout from where you get the clearest views of Chokai I have ever seen, and also decent views of Sakata City, parts of the Shonai Plains, The Sea of Japan, and if you stretch out over the railing, you can just make out the summit of Gassan behind one of the nearby mountains.

One interesting feature of the summit of Kyogakura-san is this small metallic box with all sorts of information about the place. There is even a notebook there for you to leave a message, and a few decorated rocks that keen hikers have brought up.

Yamabushi Delight: Hiking The Juninotaki Falls Trailhead up Kyogakura-san

Over the summer, one of the new things I’ve started doing is checking out the sunset for signs of the weather the next morning; Red sky at night, yamabushi delight, so the saying goes.

If the weather was good, I would get up early to watch the sunrise over Chokai-zan, even doing an Instagram Live every once in a while. For Kyogakura-san, I had done a bit of research on the Yamagatayama website and I knew there was a mountain behind Juninotaki Falls, all I needed to wait for was a red sky at night.

When the chance came, I packed my bags the night before, and left early the next morning. If I had read the website in more detail, I would have known that I had chosen the completely wrong way to hike Kyogakura-san.

In terms of places to check out, besides Juninotaki Falls and the Aizawagawa River, in all honesty this side of the mountain doesn’t have much going for it until you get near the summit. However, that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy a bit of Shinrinyoku forest bathing while you’re at it.

The Twelve Falls: Juninotaki Falls

The Juninotaki Falls Trailhead is at the end of a narrow farming road that leads into the mountains from the rice fields. It’s about a 10 minute walk from the Juninotaki Falls car park and trailhead to the actual waterfall. Follow the road over the bridge and up the hill a little while and the sign for Juninotaki Falls is on the right. There is a narrow path that leads down to the river bed where a red suspension footbridge crosses the river. Go under this bridge and Juninotaki Falls is right there.

To get to the mountain trail, return to the footbridge as if you were going to cross it. Unfortunately, the bridge is out of action at the moment, it’s quite old so don’t even consider risking it, otherwise there is a hill from where a view of all 12 of the Juninotaki Falls (Juninotaki literally means ‘The Twelve Falls’) can be seen. Just next to the bridge you will find a stairway that leads up the hill. Take this stairway and it will take you back to the main road.

Sights to see on the Juninotaki Trail

Along the way there are a number of spots from where you can see both Juninotaki Falls and the rapids of the Aizawagawa River. Keep following the road along the river and eventually you will come to another red bridge that leads to the first station from this side of Kyogakura-san.

Be warned, the climb on this side is very, very steep. I had to stop to catch my breath multiple times, and there wasn’t much to see besides the deep forest, which was actually pretty cool. There were a lot of mushrooms, however, and the path did even out at around the sixth station. Plus, around the eighth station you will find the Shumidan Rock, from where there is a great view of Chokai-zan. From there, it’s a very short hike to the lookout at the summit.

In conclusion: Kyogakura-san

My 100 Famous Mountains of Yamagata project is as much about discovering new places as it is me being a guinea pig for others. The majority of the mountains I’m visiting, I’m visiting for the first time, and besides the major mountains of Yamagata, basically none of them have any information in English, so I see it as my job to remedy that. Which is exactly why I should have done more research on Kyogakura-san.

The morning I left was one of those fine summer days with only minimal cloud cover, and I wanted to make the most of it by visiting the closest mountain on the list to my house, just a short 20 minute drive. However, looking at the map, I had definitely chosen the least eventful of the two sides. I was by myself and a little underprepared, so I went to the trailhead I knew; Juninotaki Falls.

Finding Kyogakura-san

If I had done it the other way round and gone for the Ennoji Trail first, I probably would have called it a day then and there. In the end, I’m glad I was able to be a guinea pig, as I did get to make the most of a hike up both sides. I guess that’s what happens when you’re trying to be the first (well not the first, but one of) person to do this sort of challenge, you may end up climbing a mountain the ‘wrong’ way.

Kyogakura-san might just be the closest Famous Mountain of Yamagata to 100,000+ people in Sakata and Shonai, yet no one felt the need to let me know about it. This is exactly why I instigated the 100 Mountains project, not only for myself, but for more people to discover more of the beauty of Yamagata Prefecture and the Tohoku region of North Japan.

Nearby locations worth checking out

Juninotaki Falls: The Twelve Falls

The Juninotaki Falls at the base of Kyogakura-san alone is worth the trip. The falls are a really good spot to escape the summer heat, although you’re going to want to bring bug repellent with you. There are plenty of flat rocks nearby for you to sit and enjoy your lunch, and their close proximity to the car park make them a popular location for a picnic in the warmer months.

Mount Taizo: The Epitome of Autumn Leaves in Tohoku, North Japan

Located directly behind Kyogakura-san, Taizo-san is a giant trapezoid-shaped mountain that is one of the best spots in Tohoku, North Japan, to take in the autumn leaves. The paths up Taizo-san are very easy to walk on, and the corridor of autumn leaves that awaits you heavenly. Not to mention, the Akaha lookout near the summit of Taizo-san is simply breathtaking.

Aiai Hirata Onsen Hot Springs

People from NZ are used to seeing hills covered in buildings, but for some reason this isn’t very common in the rural parts of Japan. Aiai Hirata Onsen Hot Springs is an exception. Located atop a low mountain that looks over the Shonai Plains out to The Sea of Japan, Aiai Hirata Onsen Hot Springs are probably my favourite public hot springs in Shonai.

Chokai-no-Mori Mountain Forest Park

Chokai-no-Mori is a forest park in the hills behind Matsuyama that has a lookout, a campground, a ski field (one that’s open in summer at that!), and even an observatory. Chokai-no-Mori offers great views of Chokai-zan to one side, and the Shonai Plains, Sea of Japan, and Dewa Sanzan to the other. The low-lying mountain is also popular for cycling up and down, the perfect challenge for those on two wheels!

The Former Castle Town of Matsuyama

Matsuyama is a former castle town on the outskirts of Sakata City. Parts of the castle are still very much visible, and the Matsuyama Cultural Heritage Museum is a great place to explore artifacts from the surrounding area.

The Japan Heritage Gardens of Sokoji Temple

Sokoji Temple is located in a forest at the back of Matsuyama just before the road heads up the mountain. Sokoji is famous for its national heritage Zen garden, Horaien, one of the top four gardens in the Shonai area (the others being off the top of my head: Gyokusenji Temple, the Chido Museum, and Seienkaku near Sakata Station).

Somokusha Cafe

Somokusha Cafe is my go-to cafe for freshly roasted coffee beans. The cafe is run by the very lovely Natsuko-san, and serves all manner of caffeinated beverages with traditional Japanese sweets (think sweet red bean paste). The beans roasted at Somokusha are always fresh, and there is plenty of variety available to keep this coffee nut sane.

The Grandest Waterfall in Yamagata: Tamasudare Falls

Tamasudare Falls is another popular waterfall in Sakata City. At 64m in height, Tamasudare is the tallest waterfall in Yamagata Prefecture, the prefecture with the most waterfalls in the whole of Japan. Legend has it that Tamasudare was named by Kukai AKA Kobo Daishi, who likened it to Buddhist prayer beads (tama) and Sudare bamboo shades often seen over windows during summer. Tamasudare is also a popular destination for cyclists and picnickers alike.

Omatsuya Restaurant

Omatsuya is a restaurant serving local delicacies from recipes of old in a Kominka traditional farm house. Omatsuya is a great spot to chill in an authentic Japanese environment surrounded by rice fields and mountains.

MT. KYOGAKURA

経ヶ蔵山 | きょうがくらさん

Kyogakurasan, Mt. Kyogakura, Mt. Kyogakurasan

Mt. Kyogakura (経ヶ蔵山 きょうがくらさん) is a 474m (1555 ft.) peak in the Shonai region of Yamagata prefecture best climbed from May to October. Mt. Kyogakura is a level 2 in terms of physical demand, which means it is relatively easy to hike, has a A technical grade, which means it requires little expertise, and you want to allow at least 3 hours for a climb.

Mountain Range

Mt. Kyogakura

Region

Shonai

Elevation

474m (1555 ft.)

Technical Demand

A (easiest)

Physical Demand

2 (a little tough)

Trails

Two: 1) Ennoji Trail (3 hours return) 2) Juninotaki Trail (3 hours return)

Best time to climb

May to October

Day trip possible?

Yes

Minimum Time Required

3 hours

PDF Maps by TheHokkaidoCartographer and JapanWilds.org. See all here.

100 Mountains of Yamagata, Ancient paths and trails, Autumn Leaves, Buddhist Temples and Shinto Shrines, Forest Bathing, Half-day hikes, Hard to reach, Historical Hikes, Japan, Japanese, Mountains below 500m, Myths and Legends, Onsen Hot Springs, Sakata City, Shonai Region, Short hikes, Shugendo Mountains, Waterfalls, yamabushi

YAMABUSHI NEWSLETTER